A Conversation with Jeffrey Hatcher

by Resident Dramaturg Robyn Quick

Jeffrey Hatcher is known for originals plays such as Compleat Female Stage Beauty and Three Viewings, as well as numerous adaptations for the stage. With Dial M for Murder, Everyman presents our third production of an adaptation by Jeffrey Hatcher, following Turn of the Screw in 2008 and Wait Until Dark in 2016.

Dramaturg Robyn Quick corresponded with Jeffrey Hatcher about his 2023 adaption of Dial M for Murder.

RQ: Very early in your career as a playwright, you began writing adaptations of previous works. What drew you to adapting existing works for the stage?

JH: Ambition. In the early 1990s, I saw friends of mine adapting books and plays, and I thought, “Why am I not getting in on this?” So, I wrote letters to a dozen or more artistic directors asking if there was a book they’d always wanted to see adapted, one that had never been attempted or one that had been adapted but perhaps not well. The most interesting response I received was from Greg Leaming who was artistic director at Portland Stage in Maine, saying that he’d always wanted to see a really good, really scary, highly theatrical version of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. Greg and I came up with a two-actor version that’s been staged hundreds of times over the last 25 years.

RQ: In your book The Art and Craft of Playwriting, you state, “Craft is the vehicle of talent and the imagination.” Are there elements of the playwright’s craft that are particularly applicable to writing adaptations or do you employ similar principles to both adaptations and original works?

JH: A solid understanding of craft is essential in adaptation. It provides you with the tools to answer questions like, “Does this book lend itself to dramatic form on stage?” For example, some novels can be adapted into dramatic form for film or television but don’t work well within the confines of live performance. In reading the source material, you’ve got to ask yourself: “Is there already a protagonist the audience can identify with? Are there cliffhangers in the text that move the plot forward in the way a well-crafted play must move? Is the book already leaning towards the stage?”

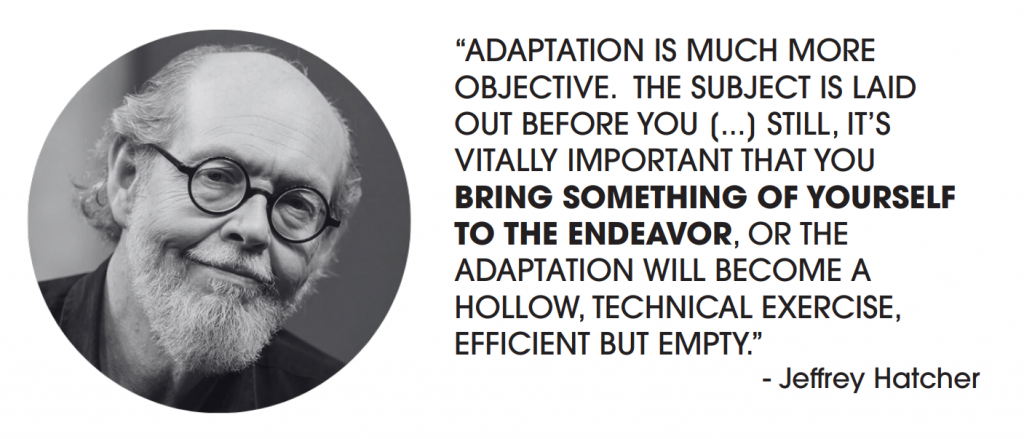

Original work is subjective. It requires exploration, imagination, and, foremost, inspiration. Adaptation is much more objective. The subject is laid out before you. Someone else has already conceived the story and brought it to a conclusion. You don’t identify with it as much as you do with your own work. Still, it’s vitally important that you bring something of yourself to the endeavor, or the adaptation will become a hollow, technical exercise, efficient but empty.

RQ: What did writing original works teach you about crafting adaptations and vice versa?

JH: I’ve learned an enormous amount from adapting other people’s books and plays. Adaptation forces you to think about structure. It develops those muscles, which is useful when you go back to your own stuff.

RQ: When you adapted Frederick Knott’s Wait Until Dark, you told The Minneapolis Post, “Frederick Knott will always be known for Dial M for Murder. That’s the perfect one.” What do you think is perfect about Dial M and how did your assessment inform or inspire the qualities in the play that you wanted to be part of your adaptation?

JH: Henry James has a quote about “the drama” that describes it as being akin to “…a box of fixed dimensions and inelastic material into which a mass of precious things are to be packed away. It is a problem in ingenuity of the most interesting kind. The precious things in question seem out of all proportion to the compass of the receptacle. But the artist has an assurance that with patience and skill a place may be made for each and nothing need be clipped or crumpled, squeezed or damaged. The false dramatist either knocks out the sides of his box or plays the deuce with the contents. The real one gets down on his knees, disposes of his goods tentatively, this, that and the other way, loses his temper but keeps his ideal, and at last rises in triumph, having packed his coffer in the one way that is mathematically right. It closes perfectly and the lock turns with a click. Between one object and another you cannot insert the point of a pen knife.”

Frederick Knott created one of those perfect boxes with Dial M for Murder. Its perfection has to do with its clockwork mechanism plot, its continuous forward motion, the well-timed reveals and reversals, its sleight of hand in shifting audience allegiance from victim to murderer, back to victim again. All this is so beautifully put together that it was daunting to adapt the play because the first rule of any adaptation of an existing play is “Don’t screw up what already works.” Fortunately, I was able to find places to massage the text, develop the characters and add a few more twists without jarring the mechanism.

RQ: Your adaptation of Dial M for Murder maintains the play’s original setting of London in 1952, but you are, of course, writing from and for our own time and place. What considerations informed that balance of crafting an experience that depicts the play’s original time and place while also speaking to us and our time?

JH: The play’s plot requires that it takes place in time before cell phones and card keys and things of that sort. In that sense, it’s very much a period piece. But by looking at that time from the perspective of today, you can excavate many of the subtextual elements in the script. By changing the gender of one of the characters, we found that it immediately upped the stakes for Margot, the play’s heroine, and made the secrets she’s keeping much more dangerous, especially in the context of 1950s upper-class London. Also, in the original, Tony “gaslights” Margot, so we built on that to give that notion a contemporary spin.

RQ: To return to the subject of the craft of writing, a compelling feature of your adaptation is the way it makes use of the character of the writer to weave reflections about the craft of writing a thriller through the thriller you have written. What are some ways you crafted your adaptation to highlight those features of a good thriller that Maxine outlines in the play?

JH: I was able to use Maxine to comment on the very kind of play the audience is watching: a stage thriller. It’s self-conscious, but she’s the kind of character who likes to expound on these things. Her meta commentary is employed three times: (1) when Maxine is talking about the premise for a book she’s writing, but she’s really sending a message to Margot; (2) when she’s on the BBC interview and we hear her talking about murders and motives while the attempted killing of Margot is taking place; and (3) when she’s trying to figure out how to save Margot and applies the rules of thriller writing to the crime that Tony has conceived and executed.

RQ: What did you find compelling about Frederick Knott’s Dial M For Murder? What do you hope audiences will find compelling about your version?

JH: The joy of plot, the joy of the pieces fitting together, Knott had an almost unerring sense of when to drop a surprise or throw a wrench into his own machinations, forcing his characters to change course in an instant. And there’s the style of the play. It’s very much a mid-century confection, as is Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 version with Grace Kelly and Ray Milland. It’s a world of Dior gowns and dry martinis, tuxedos and cigarette boxes. Audiences love that sort of thing. I know I do.

RQ: To borrow a question you once asked of Jose Rivera, you have written for film and television, but keep coming back to the theatre. Why?

JH: I’m at home in the theater, I understand the theater. I like writing for film and television, and I think I’ve learned a lot in 25 years, but it’s not my home. It’s more like a second home, a vacation house that I visit a lot but still haven’t quite mastered. As much as I enjoy film and television writing, I can live without them, but I can’t live without the theater.